Happiness, like most things in life, can be scientifically predicted. At least some of it can some of the time. You might be subject to the Happiness U-Curve if you’re not happy. What is the Happiness U-Curve? I’m glad you asked. Let me explain.

I was fascinated when I first came across research on the topic conducted by economists Andrew Oswald of the University of Warwick and David Blanchflower of Dartmouth College. Their findings appear in the journal Social Science & Medicine. [See reference at the end of this article.]

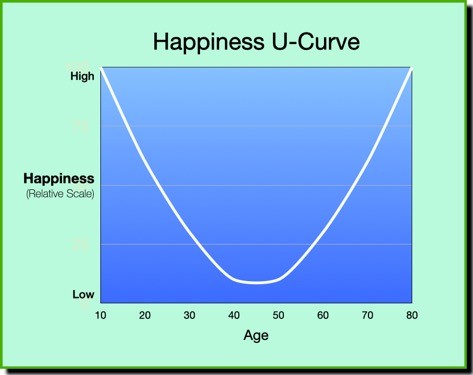

The study found an extraordinarily consistent pattern — globally — in depression and happiness levels. While previous studies of our life course suggested that psychological well-being stayed relatively flat and uniform as we age, their analysis — based on data from two million people in over 80 nations — found happiness levels followed a U-shaped curve.

Happiness tends to be higher towards the start and end of our lives but leaves us most miserable in middle age.

The study also revealed a difference between men and women. Unhappiness reached a peak at around 40 years of age for women and 50 years of age for men.

The authors believe that the U-shaped effect stems from something deep inside human beings. All kinds of people show signs of mid-life depression. It is not caused by having young children in the house, divorce, or changes in jobs or income.

In the author’s words,

“Some people suffer more than others, but the average effect is large in our data. It happens to men and women, single and married people, rich and poor, and those with and without children. Nobody knows why we see this consistency.”

Why does this happen?

What causes this U-shaped curve, and its similar shape in different parts of the developed and even often developing world, is unknown.

One possibility is that “individuals learn to adapt to their strengths and weaknesses, and in mid-life quell their infeasible aspirations,” according to the authors.

Another possibility is that cheerful people live systematically longer.

A third possibility is that a kind of comparison process is at work in which people have seen similar-aged peers die and value more their remaining years. Perhaps people somehow learn to count their blessings.

I propose a fourth possibility: this is nothing other than a mid-life crisis. It is not the mid-life crisis popularized in modern media: the balding 50-year-old guy with a red sports car and trophy wife. Instead, I am talking about the definition of mid-life crisis formulated by Karl Jung, the protégé of Sigmund Freud.

Jung on the mid-life crisis

Jung argued that the mid-life crisis was a natural and predictable phase that resulted from our relentless pursuit of happiness “out there” in the material world. We conclude that we don’t find happiness outside ourselves in the big house, cool car, perfect spouse, or high-paying job, but within ourselves. So, we go inward and do the work to find our authentic selves and re-emerge into the world, comfortable in our skin, pursuing our passion and purpose — living a fulfilling and meaningful life.

You will not hear this version of a mid-life crisis, but I encourage you to check it out if you have any doubts.

Back to the research

Again, in the authors’ words, “It looks from the data like something happens deep inside humans. For the average person in the modern world, the dip in mental health and happiness comes on slowly not suddenly.

“Only in their 50s do most people emerge from the low period. Encouragingly, by the time you are 70, if you are still physically fit, then you can be as happy and mentally healthy as a 20-year-old.

“Perhaps realizing that such feelings are completely normal in midlife might even help individuals survive this phase better.”

Does this article help explain why you might not be happy? If you’d like to find out more, please go to www.createmydreamjob.com/

Social Science & Medicine, Volume 66, Issue 8, April 2008, pages 1733-1749

Great article.